| Danish VISLSentence AnalysisEdutainmentCorporaDictionaries |

Next: Case Grammar Up: VISL and constraint grammar Previous: VISL and constraint grammar

Strategies in Constraint Grammar

When a constraint grammar analyses a text, it does so in two steps:

mapping and constraints. In the mapping-stage you define the 'tag

space' that the constraints work in. For each word in the text you map

one or (usually) more potential tags. The word 'fast', for example,

could be an adjective or an adverb (in the meaning: 'quick') or a noun

or a verb (in the meaning: 'abstaining from food'). In the

constraint-stage you remove the incorrect tags one at a time depending

on the tags of the words in its immediate context. In the phrase 'the

fast car' the word 'fast' occurs between an article and a noun, so it

can be neither a verb nor an adverb2, thus constraining the word's ambiguity from a

quadruple ambiguity to a simple ambiguity between noun and adjective.

Lexical mapping, as that of 'fast' above, happens in the lexicon, but

syntactic mapping as the mapping of '@SUBJ' to potential subjects or

'@![]() N' to potential premodifiers of nominals is done by mapping-rules

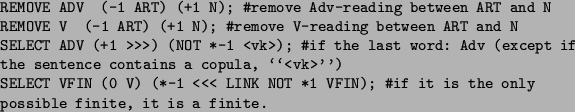

in the grammar. In figure 1.1 I show how the rules that

handle the ambiguity of 'fast' may look. The first word, REMOVE or

SELECT, tells whether to remove the particular interpretation (the

second word) from consideration, or 'select' it, i.e. remove all other

readings. The rest of the rule tells in which context to the left

('-') and to the right ('+') the rule applies. The text after '#' is

comments for the human reader only. These rules are not actual rules;

they may not achieve the intended, and may have to be modified or,

more likely, supplemented with other rules handling more specific

contexts.

N' to potential premodifiers of nominals is done by mapping-rules

in the grammar. In figure 1.1 I show how the rules that

handle the ambiguity of 'fast' may look. The first word, REMOVE or

SELECT, tells whether to remove the particular interpretation (the

second word) from consideration, or 'select' it, i.e. remove all other

readings. The rest of the rule tells in which context to the left

('-') and to the right ('+') the rule applies. The text after '#' is

comments for the human reader only. These rules are not actual rules;

they may not achieve the intended, and may have to be modified or,

more likely, supplemented with other rules handling more specific

contexts.

The mapping rules may refer to the context, though usually not in the degree that constraint rules do. This means that it is very much up to the grammar writer how to divide the workload between mapping and constraint rules. In principle you could, in one extreme, have a mapping component that maps all parts of speech to each and every word in the text, making the work for constraints a cumbersome one. In the other extreme, you could in theory make each mapping rule so complexly context-dependent that the mapping component only maps one -- the correct -- tag to each word, making the constraint component unnecessary. An example of this last strategy can be seen in my treatment of %TOP-DIST on page 4.1.3 The grammar writer will have to find his own golden middle between these two extremes. In section 4.1 I will describe the choices made in this project.

Next: Case Grammar Up: VISL and constraint grammar Previous: VISL and constraint grammar Søren Harder 2002-02-13